Picking up where we left off from Part 1, so far we’ve found a way to generate an optimal strategy for the game of Hog by recursively calculating which moves would be the best. While effective, it certainly wouldn’t have made for much of a contest if everyone who came up with this approach were tied for first. Luckily, the professor was likely aware of this possibility, and threw a wrench into the probabilistic method by forcing the strategies to work with incomplete information.

“Time Trot: A turn involves a player rolling dice, and each turn is numbered, starting from 0. If a player chooses to roll a number of dice k on turn n, and n % 8 == k, then that player gets an extra turn immediately after the current turn. However, a player cannot get an extra turn immediately after an extra turn.”

The new rule was fairly simple, and would be easy to implement as a person. A human player could keep track of what turn it is, and use their extra rolls as they wished. However, under the contest rules, the strategy “must be a deterministic function of the players’ scores and cannot track the turn number or previous actions.”

Now that the strategies were forced to work with incomplete information, the contest was a lot more interesting. My first thought was to adapt the original probabilistic method as follows:

-

Calculate the best possible move to make against a given strategy given a set of scores and the current turn number.

-

Calculate the probability that it is a certain turn number for each possible turn (0 to 7), for each possible pair of scores (0 to 99, 0 to 99)

-

Normalize each turn number and roll by the probability of it leading to a winning game

-

Find the best roll by adding up the normalized turn numbers and their rolls

TODO: Put in visualization of how data interacts.

There was of course a major flaw in the second step: to calculate the probability that a given set of scores would be a certain turn number, you needed to simulate a game between the base strategy and the strategy you were currently making. But the strategy being was made wasn’t finished yet! Uh oh. It looks like we’ll need to use an approximation: the old optimal strategy.

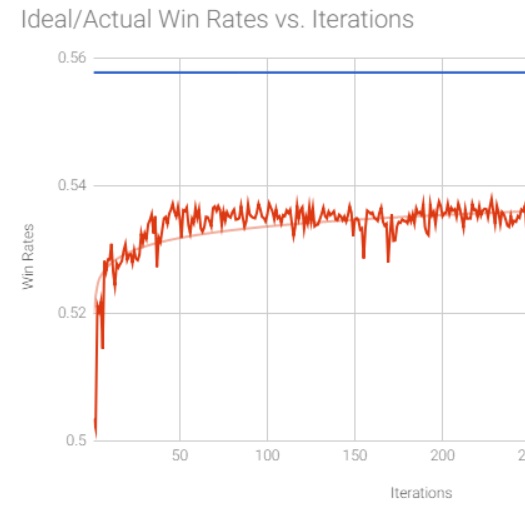

So, using the optimal strategy as the seed, as well as the approximation strategy, the new strategy reached a win rate of 0.503, beating the optimal strategy 3 tenths of a percent more often than not. Surely we could do better? The ideal (but unachievable) win rate, given complete information, was around 0.58. Was there a way to get closer to that?

The answer was: sorta. By rerunning the algorithm, this time using the output of the previous run as the approximation strategy, it actually ended up doing worse. But by repeatedly feeding the output back in like this gradual progress was made towards the ideal. After about 300+ iterations, the best win rate was around 0.537, almost halfway closer to the ideal than in the first iteration.

This was about as far as I got before I realized the contest deadline was going to make things tricky. To get that 0.537 win rate took a few hours, and a couple of attempt were ruined midway from problems with the memoization system I was using running out of memory. If I had more time, and I may look into these approaches now that I do have time, I would have tried out a few different approaches. The main ones that come to mind are creating what would be the optimal strategy if we did have complete information then “flattening” down into a 2D strategy, or doing an incremental approach where only a few outputs are changed each time. If I ever get around to that, I’ll make a part three to this saga, but for now that’s all for hog!