Full title: This title consists of two a’s, one b, two c’s, two d’s, thirty-one e’s, six f’s, four g’s, eight h’s, eleven i’s, one j, one k, three i’s, one m, eighteen n’s, seventeen o’s, one p, one q, seven r’s, twenty-eight s’s, twenty t’s, four u’s, five v’s, six w’s, three x’s, four y’s, and one z.

For real! Test it out (or just take my word for it)! The title of this post is a self-describing sentence on the typographical level. Note that I specify on a typographical level, as opposed to say a “semantic meaning” level. A statement that fits that criteria would be something like “This sentence talks about itself”. You could also have a sentence that describes itself on a “word” level, such as “This sentence has seven words in it.” Yet both of these feel somehow less interesting as the title, which is a lot more “sensitive” to minor changes. For example, if you tried to change the prefix to “This is a title…”, you would of course have to say it has four i’s instead of three. But wait, well now we have thirty-three e’s, right? But “thirty-three” adds another two e’s, so do we have thirty-five? Well now we’re back down to thirty-four, but wai… And so on, ad nauseam.

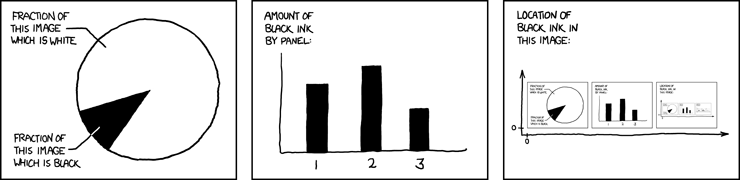

xkcd 668, “Self-description”

I first came across this concept in Douglas Hofstadter’s anthology Metamagical Themas: Questing for the Essence of Mind and Pattern. I would definitely recommmend it to anyone familiar with Hofstadter’s more popular work Gödel, Escher, Bach, although the structure of Metamagical Themas is pretty friendly to people unfamiliar with his writing style. Much like his other works, a major topic of interest is self-reference.

A Linear Algebra Attempt

So how does one produce such a sentence? One approach would be to brute force it by manually running through every combination of 26 “coefficients,” capped at some value, say forty. This would mean it would take 40^26 == 4.5*10^41 in the worst case scenario to find a working combination (or to discover that no such solution exists for a given “prefix”, in the case of this article “This title consists of”). This, in simple terms, would take a while. One reader of Hofstadtr’s column did in fact find a solution in this manner. Using a handful of clever optimizations and custom hardware, Lee Sallows was able to find a solution for the prefix “This pangram tallies” after only 2.5 months!

That sort of runtime really begs the assertion: “There has to be a better way!” When I first attempted the problem, I felt a natural approach would be through linear algebra. The essence of these self-describing sentences is the equality in the meaning of the sentence, and the composition of the sentence, i.e. solve for meaning == composition. To represent both sides of the equation, we can map each letter in the alphabet to an axis in 26-dimensional space. This isn’t unlike how in two dimensional space, we map the unit vector i to the x-axis, and j to the y-axis.

To represent the meaning side of the equation, we sum together the meaning of each coefficient (i.e. the string “two”->2, “twenty-five”->25, etc…) times the constant unit vector representing the letter (“i”->the unit vector in the positive direction of the i-dimension). This is better said in an example: “Three x’s, two y’s”. The evaluation of the meaning of this statement is a vector a component of length 3 in the x direction and 2 in the y direction.

On the other side, we have the composition of the sentence. To start, we can treat the prefix of the statement as a constant vector in our 26-dimensional character space. For example, the prefix “Prefix” is just a constant vector with components of length 1 in the p, r, e, f, i, and x directions, and 0 elsewhere. We also know that every letter is mentioned at least once, so we can add a “diagonal” vector that has a component of 1 in each direction. Finally, must add on the composition of all the coefficients from the left. This would require some function f that takes in a number, and outputs a character space vector of that numbers composition. For example, f(3) should return a vector with components of 1 in the t, h, and r directions, 2 in the e direction, and 0 elsewhere.

The problem with the problem

The downfall of this approach is rooted in the need for this function f, since it isn’t a linear operation (i.e. f(1) + f(2) != f(3)), which renders linear algebra techniques useless for solving the problem. You may have also noted that the “‘s” were not accounted for author, which relied on boolean logic that I suspected wouldn’t translate cleanly into this linear algebra approach either. It should be noted that you could use a modified version of Peano numbering as f which would be linear. In Peano’s scheme, the number zero is represented with 0, while the number one is represented as “successor of zero”, or S0. Likewise, the since two is the “successor of one” it is represented as SS0. If we cut out the postfix 0, then our “number to composition” function would be linear, but force our sentence to be read in a ssssnake-ish dialect.

The Solution

So, how can a solution be found then? The answer lies in iteration. Let’s start with a simpler prefix: “The previous sentence consists of…” This transforms the problem into something of a novelty. If we put in a dumby starter sentence, such as “The previous sentence consists of one l,” then producing a new sentence describing this one is quite trivial. We just count the letters, and then output a new sentence along the lines of “The previous sentence consists of one d, one y…” A new sentence can then be generated to describe this one, thus forming an endless list of sentences describing their predecessors. I say endless here, but intuitively we know that these sentences occupy a finite set of points in character space. Paired with the fact that our successor function is deterministic, we can conclude that at some point we run into a cycle.

This has an interesting implication: any “starter” input will eventually collapse into a loop given enough applications of our successor function. Our goal to find a self-describing sentence is instead to find a cycle of length one given a specific prefix. So, if we just generate random starting points and continue applying the successor function until we get “sucked into” a loop of length one. One way to visualize this is to imagine a sea full of whirlpools. If we wanted to find eye of an “ideal” whirlpool, which in our analogy will be one with an eye with diameter of say, 2 inches, we could check every 2x2 inch square of surface on the sea and hope to run into it. Alternatively, we could airdrop thousands of 2 inch buoys into the water. The buoy’s will naturally find their ways to the eye of every whirlpool, and if we’re lucky, one of them will find its way to the center of our ideal one.

A sea of whirlpools. Image source: “Whirl Islands” from Pokemon HeartGold & SoulSilver

Conclusion

The contents of this paragraph is left as an exercise to the reader. This concluding sentence consists of ___?