I fell down a bit of a rabbit hole the other day after seeing a post on r/sanfrancisco about a cryptic billboard in Nob Hill:

You can check the thread for the decoding method, but once solved it reveals a link to a challenge hosted by Listen Labs which I’ll be discussing my solution for. The gist of the challenge is to develop strategies for a souped up version of the secretary problem:

You’re the bouncer at a night club. Your goal is to fill the venue with N=1000 people while satisfying constraints like “at least 40% Berlin locals”, or “at least 80% wearing all black”. People arrive one by one, and you must immediately decide whether to let them in or turn them away. Your challenge is to fill the venue with as few rejections as possible while meeting all minimum requirements.

The challenge involves three different scenarios, each with constraints:

Scenario 1

Scenario 1 is the simplest scenario with only two constraints for the 1000 people in the venue:

- At least 600 young people.

- At least 600 well-dressed people.

The following statistics are also provided:

- 32.25% of the time guests are young.

- 32.25% of the time guests are well-dressed.

- Being young and being well-dressed have a correlation coefficient of ≈0.183. In other words, ≈14.4% of the time guests are both well-dressed and young.

- You can assume each guest is sampled i.i.d. from this distribution.

You can take a moment to think about how you would solve this problem. If you were as generous as possible and allowed the first 1000 people you see in, you would end up on average with 322 young people and 322 well-dressed people – well below the minimum requirement of 600 in both categories. In other words, you’re going to need to be selective. However, being too selective will increase the number of people you reject before filling the venue and make your score worse.

One detail which stood out to me was given a capacity of 1000, there must be an overlap of at least 200 between the 600 young people and 600 well-dressed people once the venue is filled, i.e. an implicit requirement:

- At least 200 people who are both young and well-dressed.

Notice also if we’re not careful with who we reject, we might end up in an unwinnable state. Say we’re in this state:

- We’ve let in 200 guests that are young and well-dressed.

- We’ve let in 401 guests that are young, but not well-dressed.

- We have 399 spaces left in the venue.

- We still need 400 well-dressed guests, which is no longer feasible.

In this case, we let in too many guests that are only young and didn’t leave enough space for 600 well-dressed guests. We can capture these constraints by defining a few variables:

space: The remaining space in the venue. This starts at 1000 and decrements every time we accept someone until it hits 0.need_y: The number of young people we still need. This starts at 600 and decrements every time we accept a young person until it hits 0.need_w: The number of well-dressed people we still need. This starts at 600 and decrements every time we accept a well-dressed person until it hits 0.

We can derive a few more values from these:

need_wy = max(0, need_y + need_w - space): The number people who are both young and well-dressed that we still need.slack_y = need_y - need_wy: The number of guests that are young but not well-dressed that we can safely accept to meet requirements.slack_w = need_w - need_wy: The number of guests that are well-dressed but not young that we can safely accept to meet requirements.

Using the slack variables, we can determine if it’s safe to allow in guests that are only

young or only well-dressed. For example, consider the state where space = 100, need_y = 50, and need_w = 100:

need_wy = max(0, 50 + 100 - 100) = 50: We need at least 50 guests that are both young and well-dressed.slack_y = 50 - 50 = 0: We do not have space to let in any guests that are young but not well-dressed.slack_w = 100 - 50 = 50: We can safely let in 50 guests that are well-dressed but not young.

Putting this logic into a function:

def accept(person: Dict[str, bool]) -> bool:

if person["young"] and person["well_dressed"]:

# No downside to accepting someone who

# meets every requirement.

return True

if person["young"] and slack_y > 0:

return True

if person["well_dressed"] and slack_w > 0:

return True

if need_w + need_y < space:

# We've fulfilled enough of the requirements

# that we can afford to let in an arbitrary

# person here.

return True

return False

In practice this strategy fills the venue and meets the requirements in an average of ≈892 rejections. Can we do better? For example, is there a way to programmatically generate an optimal set of reject/accept “policies” that we can follow at any given point in the game?

Dynamic Programming

It turns out this problem is a good candidate for dynamic programming with the goal of optimizing a function:

policy(space, need_w, need_y) -> {accept}

Here {accept} is a set containing the types of people we should accept depending on the

current state of the venue. Note that

there are four mutually exclusive types of people who we might encounter depending on different possible

combinations of attributes:

| Shorthand | Percentage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(N\) | 49.9% | People who are neither well-dressed nor young. |

| \(W\) | 17.85% | People who are only well-dressed. |

| \(Y\) | 17.85% | People who are only young. |

| \(WY\) | 14.4% | People who are both well-dressed and young. |

For example, if our policy function outputs \(\{W,Y,WY\}\) we should accept anyone who is only well-dressed, only young, or both well-dressed and young. If we want to compute the optimal policy function, we’ll also need a second function:

cost(space, need_w, need_y) -> float

Given the current state of the venue, the cost function returns the expected number of

rejections until the venue is filled and minimum requirements are met, i.e. bring space, need_w, and need_y

all to 0. This gives us our base case:

cost(0, 0, 0) = 0

In other words, when the requirements are already met the expected number of rejections until completion is 0 since we’re already done. We can also mark any infeasible state where there isn’t enough space to meet all of our requirements by giving them an infinitely high cost:

cost(100, 101, 0) = infinity

The game is unwinnable here since we need 101 well-dressed people but only have 100 spaces left. Finally, let’s consider a non-trivial example of the cost function:

cost(10, 5, 5)

Here we want to compute the expected number of rejections needed to fill the venue when there’s ten spaces left and we need five well-dressed people and five young people. It’s not clear what the optimal policy is yet, but we can start by assuming we accept anyone in \(\{W,Y,WY\}\). How many rejections will it take to find a person who qualifies? Each person we encounter has a \(17.85\% + 17.85\% + 14.4\%\) \(= 50.1\%\) chance to qualify. Using the formula for expected number of trials to first success we expect to see an acceptable person after:

\(1/p = 1/(0.501) \approx 1.99\) attempts.

Since we accept the person on the attempt we find them, on average we will reject 0.99 people. Once we’ve found an acceptable person, we need to account for the expected number of rejections we’ll make after accepting that person by recursively calling into the cost function. For simplicity, I’m making up values for the recursive calls:

- There’s a \(17.85/50.1 \approx 35.6\%\) chance the person will be \(W\). The expected cost after we accept \(W\) is

cost(9, 4, 5) = 12. - There’s a \(17.85/50.1 \approx 35.6\%\) chance the person will be \(Y\). The expected cost after we accept \(Y\) is

cost(9, 5, 4) = 12. - There’s a \(14.4/50.1 \approx 28.7\%\) chance the person will be \(WY\). The expected cost after we accept \(WY\) is

cost(9, 4, 4) = 9.

We can weight these cost values by their probabilities and sum them to calculate the expected number of people we’ll reject after accepting this one:

\((12 \times 0.356) + (12 \times 0.356)\) \(+ (9 \times 0.287) = 11.127\) rejections.

Finally, we can add together the expected number of rejections while looking for a person and the expected number of rejections after accepting a person to compute our cost:

cost(10, 5, 5) = 0.99 + 11.127 = 12.117

This cost assumes we accept anyone in the set \(\{W,Y,WY\}\) and reject everyone else.

To find the optimal policy, we can run the calculation on each of the 16 possible policies

in the power set \(\mathcal{P}(\{N,W,Y,WY\})\) and choose the

policy with the lowest cost.1 Once we find the best cost and the associated

policy, we can use those values for all future calls to cost(10, 5, 5) and

policy(10, 5, 5).

Now that we have a method for finding the optimal accept/reject policy at every possible

game state, we can recursively run this algorithm and generate a lookup table for each

of the possible \(1001 \times 601 \times 601 =\) \(361{,}562{,}201\) states of the venue.2 During

this process we end up computing cost(1000, 600, 600) = 892.4 which tells us that the

strategy is expected to fill the venue with 892.4 rejections on average.3

Scenario 2

Scenario 2 removes the young and well-dressed constraints and introduces four new ones:

- At least 750 Berlin locals.

- At least 650 techno loving people.

- At least 450 well-connected people.

- At least 300 creative people.

We also receive the following information about the distribution people are sampled from:

- 39.8% of the time guests are Berlin locals.

- 62.65% of the time guests are techno lovers.

- 47% of the time guests are well-connected.

- 6.227% of the time guests are creative.

- Well-connected and Berlin local have a correlation coefficient of ≈0.5724.

- There are correlation coefficients for all the other possible pairings of attributes, which I’m omitting for brevity.

At first it appears the number of constraints has doubled, however in practice we don’t really need to worry about the minimum of 450 well-connected people. Since the correlation with Berlin locals is high and the minimum for Berlin locals is 750, we’re almost guaranteed to satisfy the well-connected minimum while trying to meet the Berlin locals minimum. This narrows down the problem to Berlin locals, techno lovers, and creatives.

Once again we can use dynamic programming, this time computing policy and cost functions of 4 variables:

policy(space, need_b, need_t, need_c) -> {accept}

cost(space, need_b, need_t, need_c) -> float

And outputting policies that accept/reject 8 possible types of people:

| Shorthand | Percentage | Description |

|---|---|---|

N |

6.62% | People with no relevant attributes. |

B |

29.52% | People who are only Berlin local. |

T |

51.55% | People who are only techno lovers. |

C |

0.37% | People who are only creative. |

BC |

0.85% | People who are only Berlin local and creative. |

BT |

6.09% | People who are only Berlin local and techno lovers. |

TC |

1.67% | People who are only techno lovers and creative. |

BTC |

3.33%4 | People who are Berlin local, techno lovers, and creative. |

While we can reuse all of our formulas from earlier, the extra constraint drastically increases the size of the lookup table for the policy function. Assuming we encode each policy as 1 byte, the full table would need to have:

\(1001 \times 751 \times 651\) \(\times 301 = 147{,}306{,}360{,}201\) entries (137.19 GiB)

For the competition, I ended up compromising and only computing a subset of the full lookup table for use in the latter half of the game, i.e. up to:

\(500 \times 330 \times 300\) \(\times 150 = 7{,}425{,}000{,}000\) entries (6.91 GiB)

In other words, we only use the optimal strategy once we’re roughly halfway done with each of the constraints. How about for the beginning half of the game? I ended up using the same dynamic programming approach, however slightly augmenting the policy function to only take three parameters:

policy2(space, need_b + need_t, need_c) -> {accept}

In this version, we combine the constraints for Berlin locals and techno lovers into a single parameter in our policy and cost function. This allows us to drastically reduce the size of the lookup table to:

\(1001 \times (750 + 650 + 1)\) \(\times 301 = 422{,}122{,}701\) entries (402.6 MiB)

This size reduction comes at a cost: policy2 cannot distinguish

between the individual constraints for need_b and need_t. Despite this, it gives us

a good enough method to balance the tradeoffs between creative people and people

who are both Berlin local and techno lovers, which in practice are the main

bottlenecking constraints. Note we must be careful not to violate slack_b and slack_t

constraints while following policy2, since it doesn’t have enough information to account for those

on its own. In pseudo-code, the two combined policies look like:

def accept(person: Dict[str, bool]) -> bool:

if capacity < 500 and need_b < 330 and need_t < 300 and need_c < 150:

# All of our constraints have progressed enough that we can use

# the full lookup table.

return policy(capacity, need_b, need_t, need_c).allows(person)

# Trust policy2 if it accepts C, BC, TC, or BTC.

if policy2(capacity, need_b + need_t, need_c).allows(person) and person["creative"]:

return True

# Always accept BT if we need it

if person["berlin_local"] and person["techno_lover"] and need_b and need_t:

return True

# Compute slack variables for b and t to avoid

# winding up in unwinnable positions.

need_bt = max(0, need_b + need_t - space)

slack_b = need_b - need_bt - need_c

slack_t = need_t - need_bt - need_c

if person["berlin_local"]:

return slack_b > 0

if person["techno_lover"]:

return slack_t > 0

return False

This is the strategy I used for the competition, averaging around 3820 rejections before fulfilling all of the constraints.

Scenario 3

Scenario 3 discards the previous 4 constraints, and introduces 6 new ones:

- At least 500 underground veterans.

- At least 650 international people.

- At least 550 fashion forward people.

- At least 250 queer friendly people.

- At least 200 vinyl collectors.

- At least 800 German speakers.

Luckily, just like last time most of these constraints tend to solve themselves. In particular, only 3 constraints result in bottlenecks in practice: German speakers, international people, and queer friendly people. Conveniently, this means we can plug the new distribution and constraints into the dynamic programming method from Scenario 2 to generate a new strategy. This averages around 4538 rejections before fulfilling all of the constraints.

The Metagame

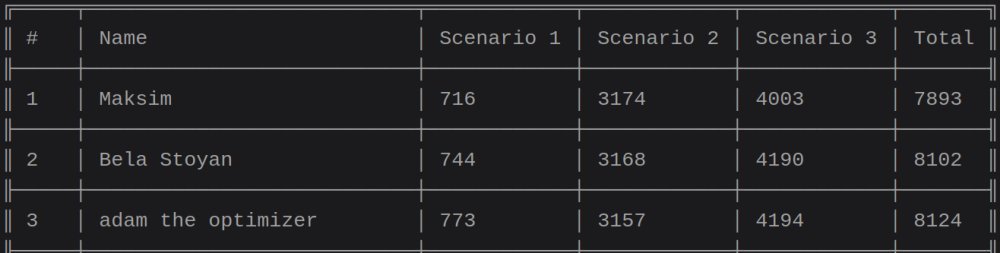

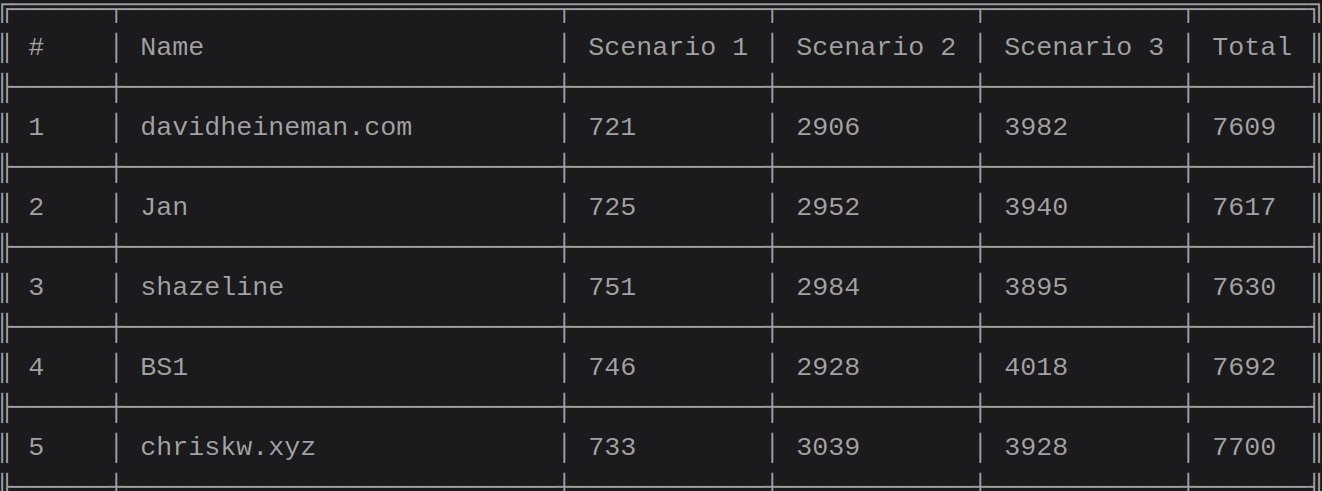

Now that we have our strategies, we can see how good they are compared to everyone else on the leaderboard, right? Unfortunately, since the problem is inherently random there’s variance in everyone’s submissions. To get a feel for this, the top of the leaderboard on the day I joined the competition looked like this:

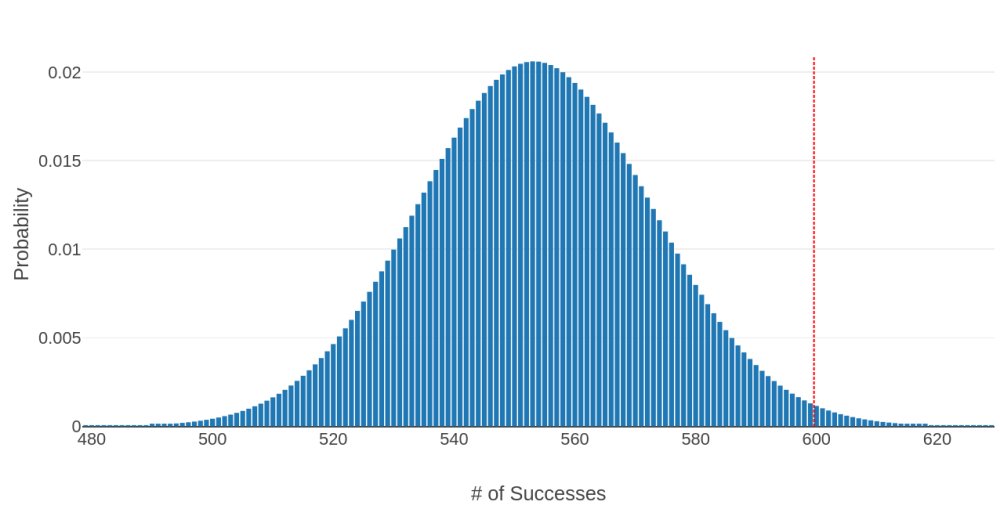

Let’s take a closer look at the score of 716 in Scenario 1. Recall that for Scenario 1, we need to fill the venue with 600 young people and 600 well-dressed people, each appearing 32.5% of the time. That means in order to get a score of 716, we need to see at least 600 young people among the first 1716 people we encounter (1000 accepts, 716 rejects). What are the odds of this? We can model this as a binomial distribution with \(p=0.3225\) and \(n=1716\):

Shoutout to stattrek.com!

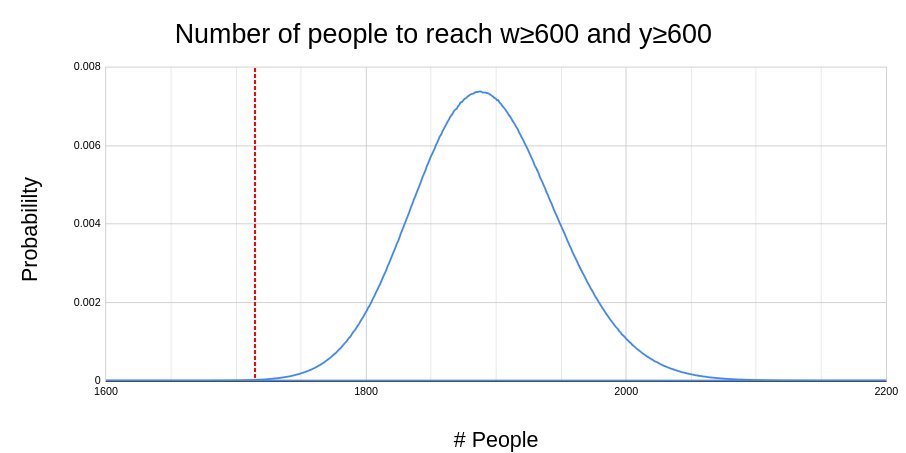

The probability that the first 1716 people will include at least 600 young people is represented by the portion of the distribution to the right of the red dotted line, which is approximately 0.9%. In other words, you need to submit your strategy for Scenario 1 about 100 times before getting a sequence where it’s even possible to fulfill the young person requirement in 1716 people or less. We also have to take into account the well-dressed requirement, which is also only possible 0.9% of the time5. Running simulations to find the minimum number of people before they’re both satisfiable, we get the following distribution:

The part of the distribution ≤1716 is almost impossible to see, but is cumulatively about 0.028%. This means roughly 1 in 3531 attempts are solvable in 716 rejections or less. In other words, having a good strategy wasn’t enough to win the contest – you also needed to submit a lot and get lucky.

Submitting a lot was a challenge in itself. To start, there was a rate limit of 10 submissions every 15 minutes, i.e. 960 submissions per day. This on its own was reasonable, however every 6 hours or so something in the networking stack would seemingly ban all traffic from IPs that had active connections. I’m not entirely sure if this was just a me problem, however from what I observed:

- The networking problem was tied to IPs, not accounts. For example, switching to a different WiFi network on the same account seemed to fix it. I assume if the organizers were actually trying to ban me, they would have disabled my account or emailed me about it.

- There was a page that showed recent submissions where you could find a 20 or so people at the top of the leaderboard constantly resubmitting up to the rate limit. Whenever I encountered the network problem, I also saw progress on everyone else’s submissions grind to halt.

- This comment on Hackernews mentions it.

My workaround for this was to rent the cheapest tier of VM from DigitalOcean for a few cents per hour and run my submissions from there. Whenever it looked like the networking issue was happening, a script automatically tore down the machine and spun up a new one with a new IP. If this really wasn’t just a me problem I’d be curious to hear what everyone else near the top of the leaderboard was doing to circumvent this.6

Anyway, once I had the consistent workaround for the networking problem I was able to briefly make it to #1 before being passed overnight. By the end of the competition I managed to finish in 5th place:

Not bad for a competition with over 1000 contestants!

Closing thoughts

Overall I really enjoyed this puzzle, although due to the non-deterministic nature of the scoring process the last few days felt a bit like a lottery.7 I’m curious to hear what strategies other contestants came up with and whether or not I left any obvious optimizations on the table.

Anyway, if you found this interesting you might also like this writeup I did about a similar competition back in 2022: Playing every game of Wordle simultaneously. Thanks for reading!

-

In practice we only need to consider 8 policies, since there’s never any downside to including \(WY\). ↩

-

spaceranges from 0 to 1000 inclusively so it has 1001 possible values. Similarly,need_yandneed_wrange from 0 to 600, with 601 possible values each. ↩ -

I suspect that the hand written strategy and the one produced by dynamic programming strategy are effectively the same, since they both have roughly same expected number of rejections. ↩

-

This information wasn’t provided by the API, and was instead estimated from the samples obtained while playing the game. ↩

-

If young and well-dressed were completely independent, we would expect the odds of getting ≥600 of both in the first 1716 to be about 1 in 10000. However since they have a positive correlation coefficient we end up with the improved odds of 1 in 3531. ↩

-

A funny side effect of this is I assume everyone near the top of the leaderboard had both a good strategy and a practical way to automatically cycle their IP to circumvent the networking problem. Given the purpose of the puzzle was to recruit people, I’m curious if it was there intentionally to filter for people with a good mix of algorithms background and practical skills. ↩

-

One of the most surprising scores by the end of the competition was a score of 2842 in Scenario 2. Based on my estimates of the distribution, the odds of getting a sequence of people where this is possible is about 1 in 150,000! ↩